|

|

| |

| Please note: All files marked with a copyright notice are subject to normal copyright restrictions. These files may, however, be downloaded for personal use. Electronically distributed texts may easily be corrupted, deliberately or by technical causes. When you base other works on such texts, double-check with a printed source if possible.

| |

|

On the Question of the Guilt of the New Left, Revolutionary Sectarianism, and the Silence of the Renegades | ||

| by Karl-Erik Tallmo |

| The radicalism of the 60's was at the beginning a rather playful phenomenon, there were music festivals and hippies and love-ins. But more dogmatic movements emerged, following the teachings of Lenin, Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, and Stalin or Trotsky. |

Suddenly there were lots of young idealistic people claiming to love freedom and justice, and in the same breath they defended the purges of Stalin, justified the murders during the cultural revolution in China, and advocated violent measures towards their own country's military and capital owners. Suddenly there were lots of young idealistic people claiming to love freedom and justice, and in the same breath they defended the purges of Stalin, justified the murders during the cultural revolution in China, and advocated violent measures towards their own country's military and capital owners.  The author of this article was an activist with the Swedish Stalinists from 1969 through 1975, at first in the organization KFML, later in the separatist group KFML(r) [1]. The author of this article was an activist with the Swedish Stalinists from 1969 through 1975, at first in the organization KFML, later in the separatist group KFML(r) [1].

At the end of the 60's, in the shadow of the Vietnam war, everybody, more or less, seemed to turn left in their political views. A general radicalism characterized the debate in several issues; the poverty of the Third world did not awake compassion any more, but solidarity and the sense of a common battle being fought. Industrial workers found - sometimes to their astonishment - that they were the objects of a virtually fanatical sympathy from rebellious students and intellectuals.

But the split of world Communism regarding how to look upon the Soviet Union was just the beginning. An almost religiously rigid quest for orthodoxy started, and as we all know the leftist organizations were split up into many factions. The struggle within the movement seemed to be as important as the struggle outside, against capitalism. Maybe the inner struggle was necessary for the members to keep their spirits up. After all, it is easier to revolt against the leaders of the movement than against the leaders of the country.

So, you can never be wrong. These mechanisms, that make this system of thought so closed, that defend it against every attack, from the inside as well as from the outside, resemble another hermetic system, psychoanalysis, where every protest is a sign of psychological resistance, only confirming the accuracy of the questioned theory or interpretation.

The yuppie era and political hangover

Then, after little more than a decade, everything changed. In the 80's came a conservative wave, and young lions played the stock market. Gordon Gekko was more fashionable than Che Guevara. Old radicals made careers in the corporate world and in the administration. Considering the prevalence of the 60's and 70's radicalism, one is not really surprised to find old rebels everywhere in the establishment of today.

The enticement of the extreme

Then, one must ask - what is so attractive about totalitarian ideology? Probably just that, the all-embracing, a system of thought with absolutely sure answers for precisely everything. And the receptive soil for all this was, presumably, young people's predisposition towards excess, purism, orthodoxy, total absorption; the exploration of extreme mental states, the precociousness and its susceptibility for all sorts of short cuts to happiness, whether it be through drugs or ideology. And of course there were hormones, ignorance, lack of experience, and a general rebelliousness towards grown-up society, which was easily applied on certain topics and conspicuous problems - the educational programs at school, the Vietnam war, Rhodesia ... It might seem a little far-fetched that this commitment also was extended to a concern for the well-being of the working class, since the activists mostly were students and intellectuals. But according to Marx, the working class is the only revolutionary class. Futhermore, in 1969 the miners up in the North of Sweden had begun a militant strike. Other groups of workers followed. We believed that this clearly indicated that a general revolutionary situation, of the kind Marx and Lenin had described, slowly drew nearer. |

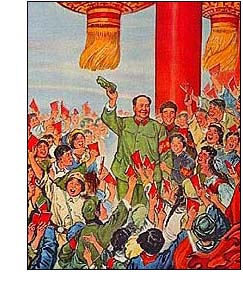

| Mao's "Little red book" became a political fetish - also for young people in the Western world. |  |

The metaphors of Mao probably caught on due to their exotic flavor, which appealed in a similar way that Indian philosophy or meditation attracted other groups. The Chairman was a helmsman. The atom bomb was a paper tiger. And there were foolish old men trying to remove mountains. The metaphors of Mao probably caught on due to their exotic flavor, which appealed in a similar way that Indian philosophy or meditation attracted other groups. The Chairman was a helmsman. The atom bomb was a paper tiger. And there were foolish old men trying to remove mountains.  Mao's "Little red book" became a fetish for many to keep in their pockets, and although those quotations often dealt with internal party affairs, they were suddenly used as a magic formula with the power supposed to convince even uninitiated people. In Sweden the cultural revolution also inspired a few very extreme sects, e.g. the so called Rebel Movement. Here, discordant members could be held in custody and were even threatened with execution. Mao's "Little red book" became a fetish for many to keep in their pockets, and although those quotations often dealt with internal party affairs, they were suddenly used as a magic formula with the power supposed to convince even uninitiated people. In Sweden the cultural revolution also inspired a few very extreme sects, e.g. the so called Rebel Movement. Here, discordant members could be held in custody and were even threatened with execution. We, who were active in some of these extreme left movements, probably suffered from some sort of megalomania, a paradoxical sense of omnipotency considering how small these sects were, and the inebriation we felt when the number of sympathizers increased, never had anything do to with our prospects in something as petty as a general election - instead it was a question of Our Historical Task. We felt like scientists, and we were but humble tools for the inevitable progress of class struggle. The revolution would come as sure as water turns into steam at a 100 degrees centigrade: When the increase of quantity, like Stalin and Engels taught, can no longer continue, instead a qualitative change occurs - the water starts boiling. We, who were active in some of these extreme left movements, probably suffered from some sort of megalomania, a paradoxical sense of omnipotency considering how small these sects were, and the inebriation we felt when the number of sympathizers increased, never had anything do to with our prospects in something as petty as a general election - instead it was a question of Our Historical Task. We felt like scientists, and we were but humble tools for the inevitable progress of class struggle. The revolution would come as sure as water turns into steam at a 100 degrees centigrade: When the increase of quantity, like Stalin and Engels taught, can no longer continue, instead a qualitative change occurs - the water starts boiling. Studies in Marxist classics were carried out diligently, and study groups covered Communist basics as well as the current editorial of the party paper - the members must be able to spread a uniform party line and argue for it. At the beginning, I found it strange that all of the questions in the course literature were put "Why is it correct to say that ..." and not "Is it correct to say that ..." But I got used to it. Studies in Marxist classics were carried out diligently, and study groups covered Communist basics as well as the current editorial of the party paper - the members must be able to spread a uniform party line and argue for it. At the beginning, I found it strange that all of the questions in the course literature were put "Why is it correct to say that ..." and not "Is it correct to say that ..." But I got used to it. Most of us were under 20. We were deadly serious and truly believed that we bore history on our slender shoulders. At the same time we developed a sort of self-critical sense of humour, but this did not help us see. Rather, the irony helped us to stay blind, it embedded and toned down the ridicule of our grand words. You could, for example, say - with a wry little smile - "I went out for a beer with the politburo yesterday." You felt important and comical at the same time. Or, you could burst out with a few bombastic phrases from the Communist Manifesto, something about how the bourgeoisie had drowned out the heavenly ecstacies of religious fervor and chivalrous enthusiasm in the icy water of egotistical calculation. Then came that embarrassed but admiring smile again. Most of us were under 20. We were deadly serious and truly believed that we bore history on our slender shoulders. At the same time we developed a sort of self-critical sense of humour, but this did not help us see. Rather, the irony helped us to stay blind, it embedded and toned down the ridicule of our grand words. You could, for example, say - with a wry little smile - "I went out for a beer with the politburo yesterday." You felt important and comical at the same time. Or, you could burst out with a few bombastic phrases from the Communist Manifesto, something about how the bourgeoisie had drowned out the heavenly ecstacies of religious fervor and chivalrous enthusiasm in the icy water of egotistical calculation. Then came that embarrassed but admiring smile again.

Violence and terror

In 1972 two terrorist attacks occurred, which shook the world. In May, Japanese terrorists, with connections to the Palestinian liberation organization PFLP, shot 26 persons at the airport in Lydda (Lod) in Israel.

The Swedish Stalinists obviously had an urge to stick their neck out, since the paper "The Proletarian" (issue 18/1972) approved of this action, the headline being "PFLP's Lydda action shocks the bourgeoisie". I remember how me and a few other comrades were somewhat shocked ourselves about this standpoint, but after a "study meeting" with discussions about the editorial, we accepted it, and were even a little proud that we in this way distinguished ourselves from other "petty bourgeois" leftist groups.

To those forces that try to use the bikers for their purposes – upper-class brats of the Democratic Alliance, von Sydow Jr (we know it's you), and others – to you we say: – You use 16 to 18-year-old political cowards for your dirty fascist purposes. Dare to show yourselves, Democratic Alliance, von Sydow and the rest of you rich man's children! Step out of the darkness in your upper-class appartments and stand face to face with the working class, you cowardly fascist pigs! Confront us openly and we will boldly counter you, we will meet you with all the decisive organized and revolutionary violence, which the advanced workers are mighty in their class hatred against you.// And the power of our class hatred, you rich men and rich men's sons, is excessive, for it strengthens ourselves every day we see one of us break down in the inhumane compulsive work in your factories, the daily exploitation to the last drop of what our bodies can manage, or when risking our lives, getting mutilated or lacerated to death. All this to feed you, owners of the factories.// We will confront you and we will hunt you down violently.Regarding attitudes towards Stalin, the original KFML sometimes claimed that Stalin was "70 percent good and 30 percent bad". The separatists in KFML(r), however, insolently announced that Stalin was a 100 percent good. To emphasize this fact, they published a biography in 1972, titled "J.V. Stalin - the steel-hard leader of the Bolsheviks". The chairman of KFML(r), Frank Baude, wrote a special preface, where he says that some leftist groups consider Stalin to be both good and bad. "What these alleged faults of Stalin would consist of, they can never explain," Baude says and goes on: "The critique against Stalin for being to hard against the class enemy is a bourgeois argument. For a Communist it can never be a bad thing to treat class enemies in a hard way."  The Art Bin has also - in connection with this article - published the complete court proceedings report (in English) from the Moscow trials of 1936, as it was published by the People's Commissariat of Justice in the Soviet Union. These reports were also published in Swedish the same year, a task taken care of by the Communist Party of Sweden (SKP). It is highly remarkable, that those proceedings reports - which show that the trials were based almost solely on confessions, an extremely dubious judicial principle - could be used as propaganda for Communism. Furthermore, René Coeckelberghs' Trotskyite publishing firm reprinted a facsimile of this book in 1971, to demonstrate the horrors of Stalinism. Then, the real irony was that the Stalinists themselves started selling this new "Trotskyite edition" in their own book stores. The circle was closed. The Art Bin has also - in connection with this article - published the complete court proceedings report (in English) from the Moscow trials of 1936, as it was published by the People's Commissariat of Justice in the Soviet Union. These reports were also published in Swedish the same year, a task taken care of by the Communist Party of Sweden (SKP). It is highly remarkable, that those proceedings reports - which show that the trials were based almost solely on confessions, an extremely dubious judicial principle - could be used as propaganda for Communism. Furthermore, René Coeckelberghs' Trotskyite publishing firm reprinted a facsimile of this book in 1971, to demonstrate the horrors of Stalinism. Then, the real irony was that the Stalinists themselves started selling this new "Trotskyite edition" in their own book stores. The circle was closed.

The book "J.V. Stalin - the steel-hard leader of the Bolsheviks" (1972).

Then Franklin does his best to prove that Stalin was a beloved ally to the peoples of China, Vietnam, Korea and Albania in their struggle for liberty. Inter alia, Franklin quotes the American ambassador to Moscow (1936-38), Joseph E. Davies, whose book "Mission to Moscow" (1941) is one of the most notorious publications in the West, a diary where Stalin's purges and the Moscow trials are justified.

Yes, totalitarians are always upset about torture and mass murder - in the opposing camp. But if Trotskyites can be depicted as agents for Nazi-Germany, then the barbarous methods of fascism may conveniently be justified and used also by Communists.

The renegades

Renegades have mostly given rise to only mockery or ridicule within the Communist ranks, rather than reflection and revaluation. I remember how someone left the student organization Clarté, which was closely related to the KFML, and then joined the Pentecostal Movement instead. He turned to the press and claimed that the Communists had made lists of people to be killed when a revolutionary situation arose. Personally, I never heard of or saw any such lists, neither in the KFML nor in the KFML(r), but if any members worried about such things, they did not have to. Just the fact that the defector had turned to religion, was somehow enough to invalidate him as a witness to the truth.

The death of an illusion

Those who joined Marxist organizations because they wanted to rebel against authorities must have been deeply disappointed - or maybe they just changed their aspirations. And nobody can claim that the ultimate objective, the dictatorship of the proletariat, would be some sort of grass-roots movement.

Note:

1. The KFML was an acronym for "Kommunistiska förbundet marxist-leninisterna" (The Communist League of Marxist-Leninists). The separatist group KFML(r) added one letter, signifying "revolutionaries". In 1977 the league changed its name to KPML(r) - where P stands for party - and in 2005 the name was shortened to the Communist Party. To an outsider, this may seem trivial, but in a communist context, the issue of party formation is something quite crucial. Before a communist organization may call itself a party, it should have rooted in the working class, and the organization should also have developed a so-called class analysis of the society in which it operates. In KFML(r) prior to 1975, this was regarded to be a matter of scientific Marxist method, an extensive economic-political work spanning several years. One were to execute a correct analysis of all the classes and strata in the Swedish society, and how these possibly would stand in a revolutionary situation; which of them were likely to be allies, who were enemies, and which groups might move in one direction or the other. The fact that KFML(r) formed a party already in 1977 most surely reflects a new approach to this process.

[Go Back] |

This article is © copyright Karl-Erik Tallmo 1997. Two additions to the text were made in 2011.