|

|

| |

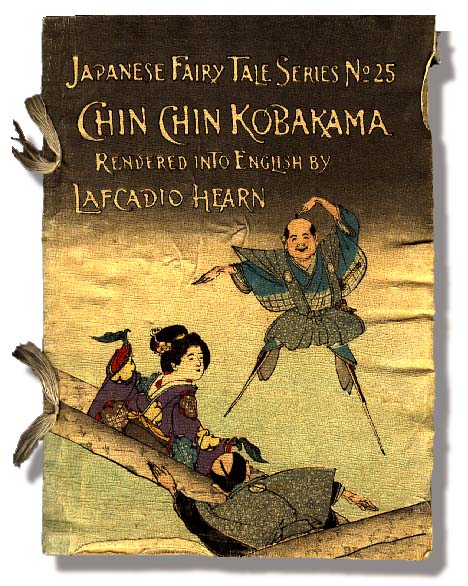

Chin Chin Kobakama

|

In his preface to this small and beautiful book, Lafcadio Hearn talks about mischivous children and ghosts in Japan. And he knew a lot about the adult world's strange demands on children, and the fears of a small child. His own childhood was - to put it bluntly - a real mess. He was born in Greece (1850) and grew up in Ireland, England, France and the US, living with his mother, his aunt, with his aunts chamber maid, with a brother in law ... Aunt Sarah locked him up at night in a dark room to cure him from his fear of darkness. Well, he grew up and became a sort of Grimm brother, who notated and collected folkloristic tales and legends, first in Greece and later in Japan. When he arrived at Yokohama in 1890, he immediately felt that this was his new homeland. At last a place where he was treated with respect and found friends. Originally he came to Japan because of an assignment for Harper's Magazine, but he quit journalism and started working as a schoolteacher in English. He married, had four children, and in 1896 he adopted a Japanese name, Koizumi Yakumo. Between 1896 and 1903, Hearn worked as a professor of English literature at the Imperial University of Tokyo. During this time he wrote, for instance, "Exotics and Retrospective" (1898), "In Ghostly Japan" (1899), "Shadowings" (1900), and "A Japanese Miscellany" (1901). Hearn died in 1904. The small book that is published here, Chin Chin Kobakama, is from 1905, printed in Tokyo on double folded, very soft crêpe paper and bound with silk. The format on-screen is approximately the natural size. /KET The small book that is published here, Chin Chin Kobakama, is from 1905, printed in Tokyo on double folded, very soft crêpe paper and bound with silk. The format on-screen is approximately the natural size. /KET

(Lafcadio Hearn's untitled Preface) The floor of a Japanese room is covered with beautiful thick soft mats of woven reeds. They fit very closely together, so that you can just slip a knife-blade between them. They are changed once every year, and are kept very clean. The Japanese never wear shoes in the house, and do not use chairs or furniture such as English people use. They sit, sleep, eat, and sometimes even write upon the floor. So the mats must be kept very clean indeed, and Japanese children are taught, just as soon as they can speak, never to spoil or dirty the mats. Now Japanese children are really very good. All traveIlers, who have written pleasant books about Japan, declare that Japanese children are much more obedient than English children and much less mischievous. They do not spoil and dirty things, and they do not even break their own toys. A little Japanese girl does not break her doll. No, she takes great care of it, and keeps it even after she becomes a woman and is married. When she becomes a mother, and has a daughter, she gives the doll to that little daughter. And the child takes the same care of the doll that her mother did, and preserves it until she grows up; and gives it at last to her own children, who play with it just as nicely as their grandmother did. So I, - who am writing this little story for you, - have seen in Japan, dolls more than a hundred years old, looking just as pretty as when they were new. This will show you how very good Japanese children are; and you will be able to understand why the floor of a Japanese room is nearly always kept clean, - not scratched and spoiled by mischievous play. You ask me whether all, all Japanese children are as good as that? Well - no, there are a few, a very few naughty ones. And what happens to the mats in the houses of these naughty children? Nothing very bad - because there are fairies who take care of the mats. These fairies tease and frighten children who dirty or spoil the mats. At least - they used to tease and frighten such mischievous children. I am not quite sure whether those little fairies still live in Japan, - because the new railways and the telegraph-poles have frightened a great many fairies away. But here is a little story about them: - |